Everyday Life in Nagasaki Before the Atomic Bombing School Life During Wartime

目次

Abstract

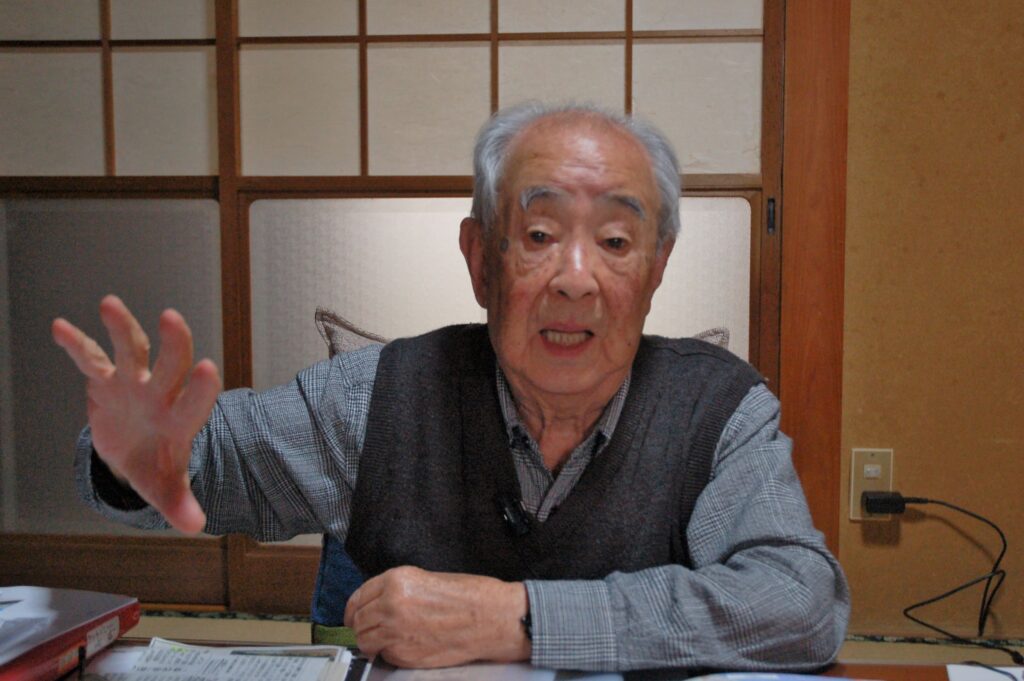

This presentation is based on photos and interviews with Mr. Hisamichi Jouzaki, who was a student at a prewar junior high school (equivalent to today’s middle and high school) in Nagasaki. It shows what school was like before the atomic bomb was dropped, the friendships he enjoyed, and how school life changed as the war intensified. At Chinzei Gakuin Middle School, a Christian mission school, foreign missionaries were involved in teaching until the war grew more severe. Through this material, you can learn about the unique school life in Nagasaki at that time.

Jouzaki Hisamichi

Born in 1928. At age 17, he was exposed to the atomic bomb at the Mitsubishi Weapons Factory in Morimachi, about 1.2 kilometers from the hypocenter. At the time, he was a second-year student in Chinzei Gakuin Middle School’s attached division. As part of student labor mobilization, he worked at the Third Finishing Department of the Mitsubishi Weapons Factory in Morimachi, assembling torpedoes, performing solder plating, machining parts, and other tasks.

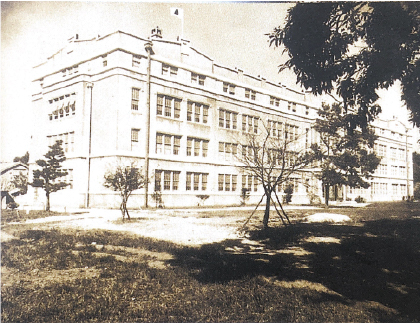

Chinsei Gakuin Junior High School

Provided by: Chinzei Gakuin Educational Corporation

I enrolled in the old Chinzei Gakuin Middle School in 1940 (Showa 15).

Our family was neither well-off enough to usually afford private school nor were we Christians, but a relative of ours happened to be a military officer assigned to Chinzei. Through that connection, both my older brother and I got into Chinzei.

At that time, the old-style junior high school had a five-year program, covering what would now be considered middle school through high school. Chinzei Gakuin was a Christian mission school. It was founded in 1881 (Meiji 14) and relocated to the site shown in the photo in 1930 (Showa 5). After the atomic bombing, it moved to Isahaya City.

Photo after the bombing

Courtesy of the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum

Students at that time

A picture with classmates. Mr. Jouzaki is in the top row, second from the right.

Provided by: Chinzei Gakuin Educational Corporation

Because my home was quite far from school, I took the streetcar every day. It passed in front of Suwa Shrine. Whenever it did, all students in the car, regardless of school, would remove their caps and bow politely. Adults on board would also bow their heads. Back then, it was natural for everyone to show respect when passing by a sacred place.

Mr. Jouzaki grew up in Katafuchi Town in Nagasaki City. Back then, there were fields around his house, and the landlord was a farming family. His mother often made pickled red turnips from produce they received from them. Later, his family moved to Inasa Town, closer to Chinzei Gakuin.

mission school

Around 1943 (Showa 18). Inside the school’s dojo (training hall). The boy lying down in the front right is Mr. Jouzaki.

Because Chinzei was a mission school, all students would gather in the auditorium each morning for worship and prayer. During worship, everyone would quietly say ‘Amen’ with no distractions. But once we were back in the corridor, I remember whispering silly things like, ‘Amen, somen!’ with my friends and giggling about it.”(Translator’s note: “Amen, somen” is a playful rhyme in Japanese involving “somen,” a type of thin wheat noodles.)

According to Chinzei Gakuin’s school history, Christian worship services were held even under pressure from the military government during the war. However, as the war worsened, this pressure grew stronger, and in 1944 (Showa 19), the school was forced to suspend worship services.

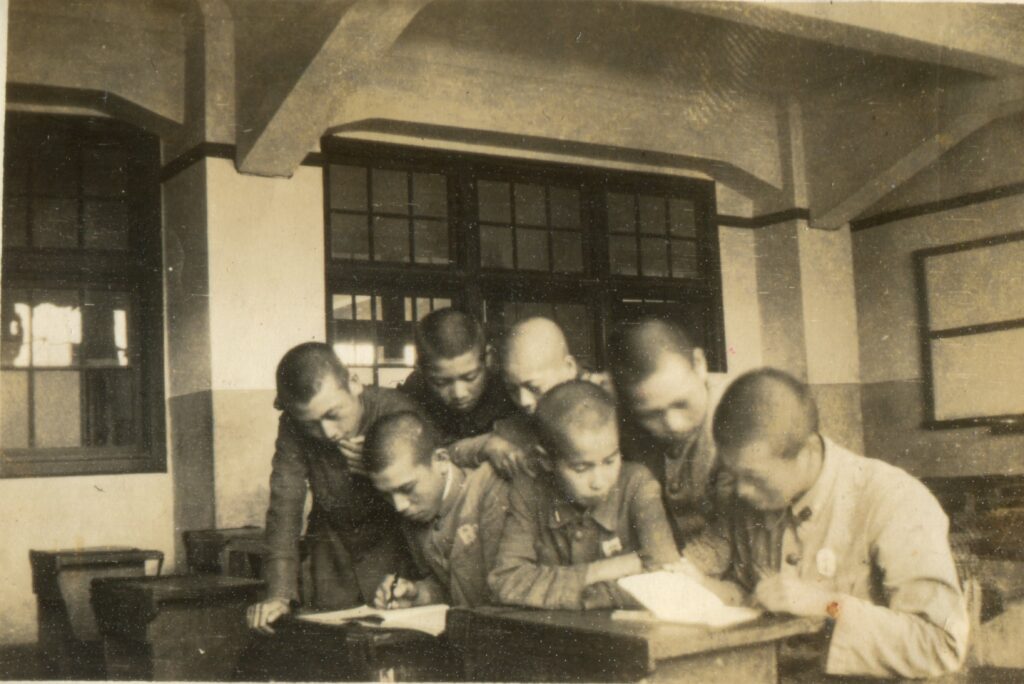

English Study

Around 1943 (Showa 18). In a classroom at school. Mr. Jouzaki is the third from the right.

We even had English classes at school. To learn vocabulary, we bought blank cards from the stationery store, writing the English word on one side and the Japanese meaning on the other. When I started at Chinzei, there was actually an American missionary teacher, so even when people began calling Americans ‘kichiku Beiei’ (a wartime slur meaning ‘brutal American and British beasts’), I personally never felt that way. After the war, during the occupation, my English was useful for talking with American soldiers.

Back then, English was sometimes called an “enemy language,” but Chinzei Gakuin continued to teach English even during the war. When Mr. Jouzaki enrolled, an American who had come to Japan as a missionary was teaching at the school. However, as relations between Japan and the U.S. deteriorated, that teacher was forced to return home.

military training

We also had military training at school. Each student was issued an infantry rifle. But as you can see from the photo, I was much shorter than my friends, so I couldn’t handle the regular full-length rifle. I was issued a cavalry rifle instead (which was shorter, for shooting while on horseback). I felt embarrassed about being the only one using a different rifle.

In April 1925, the government enacted the “School Military Officer Placement Ordinance,” assigning active-duty army officers to teach military training in schools from junior high level onward. At Chinzei Gakuin, there was even an armory in the school’s basement.

When we had off-campus activities, like field trips, they actually turned into training sessions. There was a big open space, which I hear is now a golf course, where we pretended it was a battlefield. We had to spread out, run, and drop to the ground whenever the instructor yelled, ‘Get down!’ It was tough training.

Military training wasn’t just about preparing more soldiers; it was also meant to instill wartime ideology in students. Schools weren’t free places for academic study as they are today. They were used to spread militaristic thinking. After Japan’s defeat, military training in schools was abolished.

(Undated) Military training at school.Provided by: Chinzei Gakuin Educational Corporation

glider training

Around 1943 (Showa 18). In front of the school building. Some of Mr. Jouzaki’s friends pose with a glider.

Our school even offered glider training. The concept was simple: we’d pull the glider with a big rubber rope to make it lift off. We could only launch it on the school field, so it would just hover for about a meter and then descend right away. I was too short to ride, so it was mostly my taller friends who were going on to the Naval Pilot Prep (Yokaren) who practiced.

The glider was supplied by the military to teach the basics of flight. After learning basic aviation skills on the glider, physically fit and capable students would advance to Army Flight School or the Navy’s Yokaren (flight preparatory course).

Pearl Harbor attack day

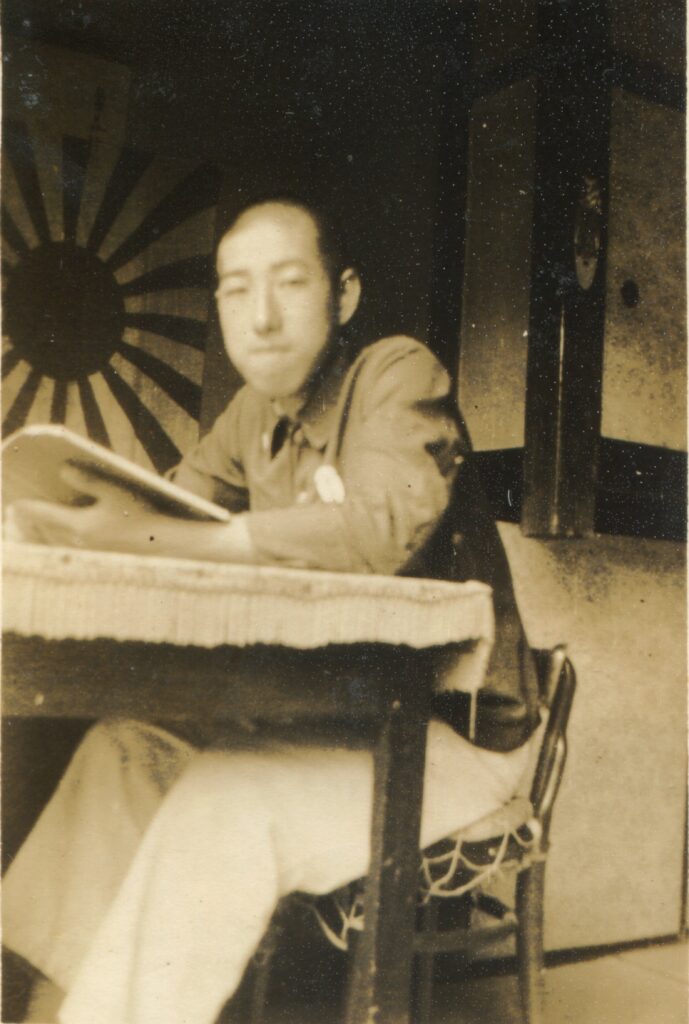

Around 1943–44 (Showa 18–19). A friend of Mr. Jouzaki who joined the Naval Pilot Prep (Yokaren).

I remember the radio broadcast on December 8, 1941, the day of the attack on Pearl Harbor. At school, we knew how huge America was, because we learned about it in class. So even if I didn’t actually believe Americans were demons, hearing that ‘Japan won a great victory’ still made me feel happy at the time.

The period when Mr. Jouzaki attended the school overlapped with Japan’s increasing involvement in the war. In 1940 (Showa 15), when he enrolled, Japan was already in the midst of the Second Sino-Japanese War. The following year, in December 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, leading to the Pacific War.

Farewell party for a friend

Around 1943–44 (Showa 18–19). A farewell gathering for friends who joined Yokaren.

*Colorized using Photoshop’s Neural Filters (AI-based colorization).

In our fourth and fifth years, some of my classmates volunteered for Yokaren or for special army officer training, so they left school to join the military. Before they left, we’d all gather at their homes for a small farewell party or sign a Japanese flag with encouraging messages. At the time, we all cheered them on—‘Go do your best!’—and we didn’t really feel sad about it.

Around 1943 (Showa 18), military personnel came directly to Chinzei Gakuin to recruit volunteers. Some of those students later died in special (kamikaze) attacks.

mobilization of students

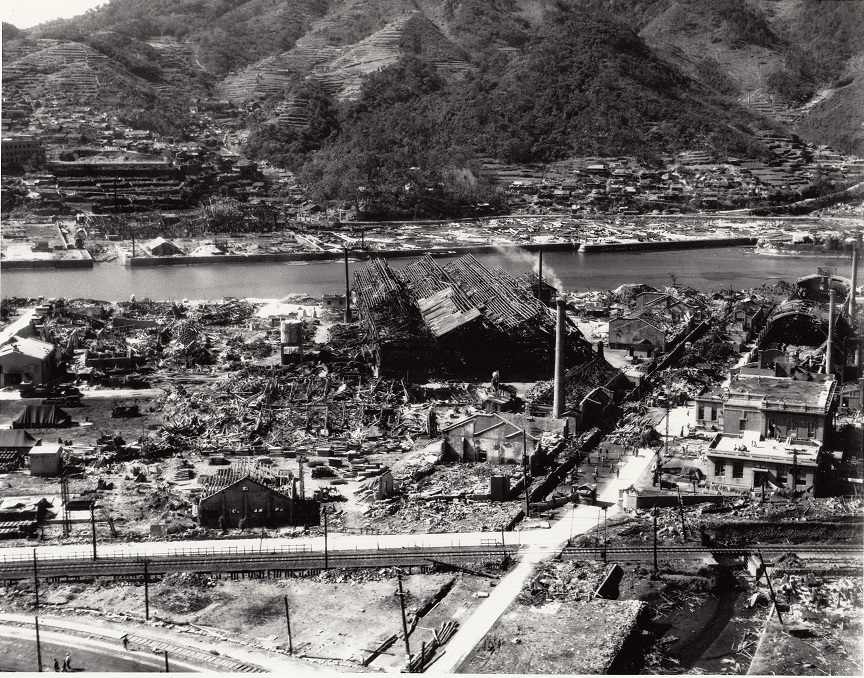

Aerial view of the Mitsubishi Nagasaki Shipyard’s Saiwaimachi and Morimachi factories after the bombing.

Provided by: Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum

Until about 1942 (Showa 17), school still felt pretty relaxed. We even played around during lunch break. But the next year, student mobilization began, and we were sent to work in weapons factories instead of attending class. I was assigned to an electrical plating line in a torpedo factory. The supervisors were strict, but oddly enough, I was good at that kind of work, so they gave me many tasks.

Around this time, many adult men were being drafted, causing severe labor shortages in factories, mines, and on farms. To fill the gap, students were pulled from school and made to work. Mr. Jouzaki was sent to the Third Finishing Department of the Mitsubishi Weapons Factory in Morimachi, Nagasaki.

August 9

Inside the finishing department at the Mitsubishi Weapons Factory in Morimachi, Nagasaki, after the bombing.Provided by: Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum

On August 9, I was inside the factory when the atomic bomb exploded. A bright, bluish-white light suddenly flashed through the skylight, and at first I thought some high-voltage line had shorted out. Then, in the next moment, the building just collapsed around us. The photo here is probably where I worked. Pieces of concrete fell on my head and back, but by some miracle, I escaped without major injuries.

Looking back, Mr. Jouzaki says, “I guess I was just lucky.” The factory was completely destroyed by the bomb, and many of the workers and mobilized students there were killed. At Chinzei Gakuin Middle School, around 140 staff and students died either on campus or at their mobilization sites.

Message

Some of my classmates joined the Yokaren program (Navy prep school) and so on. Under the circumstances at that time, going to the battlefield was considered an honor. Even so, I’m sure the parents who had to send their children off were filled with worry. I hope that seeing these photos helps people feel not only what life was like for those who were killed by the bomb, but also what it was like for those of us who survived.

Mitsuhiro Hayashida (RECNA Specially Appointed Researcher)

Ryo Sasaki (Writer)

Photo Credits:Hisamichi Jouzaki,Chinzei Gakuin Educational Corporation,Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum

Design:Maika Okubo

© Nagasaki University Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition (RECNA) / National Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Victims Memorial Hall

References and Websites

- Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum, ed. (2006). Nagasaki Atomic Bomb War Damage Records, Vol. 1, Vol. 2, Vol. 3. Nagasaki City.

- Nagasaki Centenary Chronology Editing Committee, ed. (1989). Nagasaki City 100-Year Chronology. Nagasaki City.

- Hotei Atsushi (2020). Reconstruction! Nagasaki Just Before the Atomic Bombing: A Map of August 8, 1945, Before It Was Destroyed. Nagasaki Bunken-sha.

- Sameshima Moritaka, ed. (1973). Ninety Years of Chinzei Gakuin. Chinzei Gakuin.

- Chinzei Gakuin, ed. (1981). One Hundred Years of Chinzei Gakuin. Chinzei Gakuin.

- Chinzei Gakuin (1991). 110 Years of Chinzei Gakuin: 1881–1991. 110th Anniversary Project Department of Chinzei Gakuin.

- Atomic Bomb Drop Period Student Registry Editing Committee, ed. (2011). That Day, Our Dreams Disappeared: Old Chinzei Gakuin Middle School Registry and A-Bomb Survivor Records from the Time of the Bombing: A 130th Anniversary Project. Chinzei Gakuin.