Hiroshima Before the Bomb: Everyday Life When the Atomic Bomb Dome Was Still the Industrial Promotion Hall

目次

- Abstract

- Tokuzo Hamai

- Family Structure of the Hamai Family

- Father of barber

- Barbers.

- Mother from Hawaii

- Industrial Promotion Hall

- Mutoku Kindergarten

- Kindergarten Memories

- Evacuation to Hatsukaichi

- Brother and Sister

- wall clock

- Clock pointing to 8:15.

- Memories of Nakajima Honmachi

- Message

- References and WEB sites

- Learning Material

Abstract

Nagasaki was the tenth most populous city in Japan at the time and was thriving. Its central downtown area was bustling with people, and life was affluent. However, with the onset of the Pacific War, people’s lives changed drastically as the war situation worsened. This section features a collection of photos and interviews with Seiichiro Mise, who was born and raised in “Mise Shoten,” a wholesaler of clothing, towels, and other goods in the downtown area since his grandfather’s time in the Meiji period. These materials highlight the life in downtown Nagasaki of those days.

Tokuzo Hamai

Born in 1934. At age 11, the atomic bomb exploded just 200 meters east of his home and barbershop in Nakajima Honmachi. He lost his entire family—his father, mother, 14-year-old sister, and 12-year-old brother. At the time, he had been safely evacuated to his aunt’s home in Miyauchi Village (now Hatsukaichi City). Two days after the bombing, he returned to the ruins of his home to search for his family and was exposed to residual radiation.

Family Structure of the Hamai Family

From left, second person is Tokuzo Hamai; directly behind him is his brother Tamazo. At the far right is his sister Hiroko and mother Itoyo. The man standing is his father, Jiro.

I was born on July 21, 1934, to my father Jiro and my mother Itoyo. My father ran the “Hamai Barbershop” in Nakajima Honmachi, at address 33-1. That was also our family home. I had an older sister, Hiroko, who was three years older than me, and a brother, Tamazo, two years older. There were five of us in the family, and we also had live-in apprentices working at the shop.

The area now known as Peace Memorial Park, located in the central part of Hiroshima where the Motoyasu and Honkawa rivers meet, used to be called the Nakajima District. It was one of Hiroshima’s busiest downtown areas, made up of neighborhoods like Nakajima Honmachi, Tenjin-machi, Zaimoku-machi, Kobiki-machi, Motoyanagi-machi, and Nakajima Shin-machi. According to the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb War Damage Report, just before the bombing, the district was home to approximately 1,330 households, 1,300 buildings, and 4,370 residents.

Father of barber

Jiro Hamai (far right, second row from the front), in a graduation photo from Hiroshima Barber School, taken in October 1939.

His father also taught at a barber school and hung a sign reading “Hamai Barber Research Institute” at the shop. Wearing striped trousers and a bow tie, he promoted the use of electric clippers, which were still rare at the time. The shop stayed open until around 11 p.m., after which he often went out drinking. He would sleep until noon, and his wife or students from the barber school would have to wake him up.

According to a street reconstruction map of Peace Memorial Park created by the Chugoku Shimbun in June 2000, Nakajima Honmachi, which stretched from the current site of the Atomic Bomb Cenotaph at the northern tip of the delta, was lined with cafés, movie theaters, inns, billiard halls, and corporate branch offices, including Dai-ichi Life Insurance.

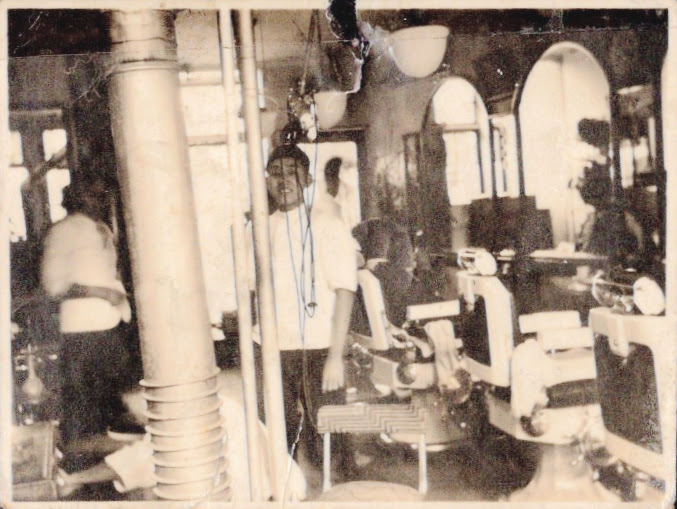

Jiro Hamai at work inside the Hamai Barber Shop.

Barbers.

Jiro Hamai (center) and live-in apprentices in front of the barbershop, taken in 1936.

After school, I’d throw down my bag and run straight outside to play, trying not to let my father catch me. The apprentices who lived at my father’s shop would smile and watch me quietly. One of them always stayed close by, keeping an eye on us kids.

The barbershop, Hamai Rihatsukan, appears in the 2016 animated film In This Corner of the World. Director Sunao Katabuchi spent six years gathering thousands of documents and visited Hiroshima numerous times to interview former residents of Nakajima Honmachi, including Mr. Hamai. The names of those who helped with the production are listed in the film’s ending credits.

The Hamai Barbershop as depicted in In This Corner of the World, showing Tokuzo’s father, mother, brother, and sister.

(C) Fumiyo Kouno / Futabasha / In This Corner of the World Production Committee

Mother from Hawaii

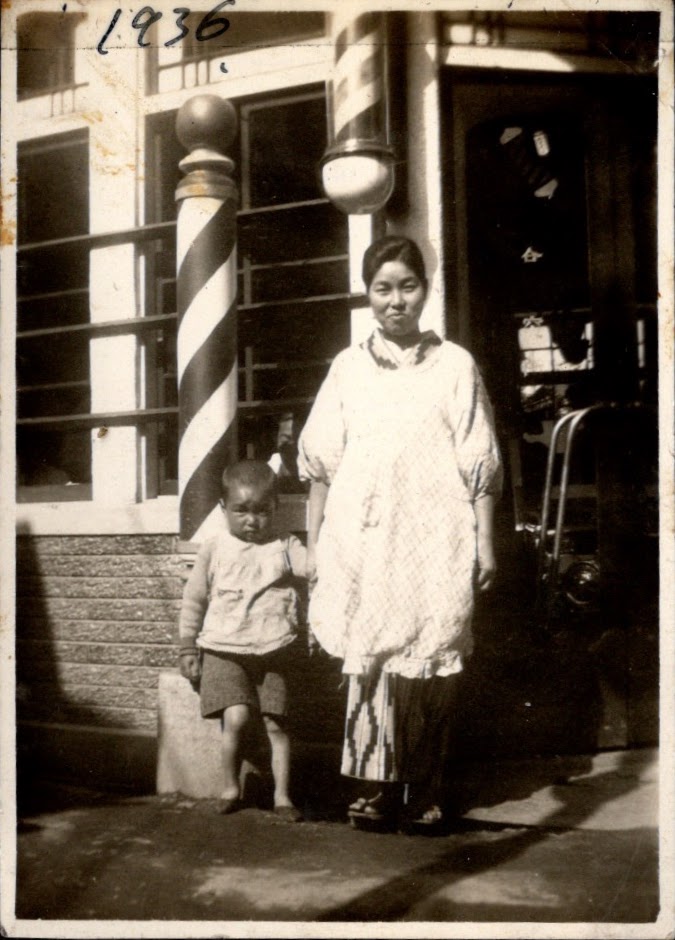

Itoyo Hamai and her young son Tokuzo (around age 2), standing in front of the barbershop, 1936.

My mother was born in Hawaii and moved back to Japan with her parents when she was in the sixth grade. My grandfather on my mother’s side ran a car repair shop in Hawaii. Since my mother spoke both Japanese and English, she stood out from the other women around her who usually wore plain kimonos and monpe pants. She liked to wear dresses and carry a bright blue parasol with floral patterns. My mother used to sew all our clothes herself, carefully making each piece on her sewing machine.

Hiroshima was Japan’s top prefecture for overseas emigration. According to the JICA Yokohama Japanese Overseas Migration Museum, more than 109,000 people left Hiroshima for other countries before and after World War II. The second-highest number came from Okinawa. Large-scale emigration from Hiroshima began in 1885 with government-sponsored migration to the Kingdom of Hawaii and later expanded to North America and Latin America. Many early emigrants planned to work abroad temporarily and return home with their earnings.

Industrial Promotion Hall

Across the river from the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, with his sister and friends.

The adult in the center was an apprentice at the shop; sitting near his feet is Hamai Tokuzo (taken in 1938).

The building now known as the Atomic Bomb Dome was once called the Industrial Promotion Hall. Inside, it had a spiral staircase, and we used to slide down its handrails for fun. In the summer, we played in the Motoyasu River, which flowed between our house and the hall, and we sometimes jumped into the river from Motoyasu Bridge to test our courage.

The Atomic Bomb Dome was originally built in 1915 as the Hiroshima Prefectural Commercial Exhibition Hall. A three-story red brick building, it featured a five-story central tower topped with an oval-shaped dome. Designed by Czech architect Jan Letzel, the building was renamed the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall and was used by government offices at the time of the bombing.

Left: Hamai Tokuzo, Right: his older brother Tamazo.

The Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall can be seen in the background. Taken in 1938.

Mutoku Kindergarten

Sports day at Mutoku Kindergarten in the fall of 1940. In the center, facing the camera, is six-year-old Hamai Tokuzo.

When my neighborhood friends started going to school, I got bored being home alone. I asked my father if I could go to kindergarten, and he sent me to Mutoku Kindergarten. Every day, I brought my lunchbox with me. During winter, they had a big charcoal-heated kotatsu to keep our lunches warm. One day, when I opened my lunch, the rice had turned completely black from being burnt.

South of Nakajima Honmachi, in an area that now covers about the southern half of Peace Memorial Park, was once called Zaimoku-machi. Near the west side of today’s Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum stood Seiganji Temple, which had a pond shaped like a gourd, a bell, and a belfry. Mutoku Kindergarten was located in one corner of that temple precinct.

Kindergarten Memories

A ceremony at Mutoku Kindergarten in 1940 to mark Kigen 2600-nen.

Hamai Tokuzo is in about the middle of the third row from the back, wearing an apron with a large mark.

I remember being scared of Nakamura-sensei, the elderly principal at my kindergarten—she often scolded me. One day at lunchtime, I pointed at someone with my chopsticks while tattling, and she yelled, “Never point at people with your chopsticks!” Because I was always getting into trouble, my mother sewed a big red daruma patch onto my apron so she could easily spot me among all the children.

In 1940, Japan commemorated Kigen 2600-nen (the 2,600th anniversary of the legendary accession of Emperor Jimmu). Events were held nationwide to mark this occasion. According to Hiroshima City, six cherry trees planted on the City Hall grounds included three “A-bombed cherry trees,” planted to celebrate the 2,600th anniversary. Although burned down to their trunks by the bombing, they still bloom each year.

Evacuation to Hatsukaichi

A funeral for my maternal grandmother in Hara Village (now part of Hatsukaichi City), near Miyauchi Village where I was later evacuated.

I am the smaller child on the left, beside my father Jiro and brother Tamazo (photo from 1939).

Where I was evacuated, the electricity was cut off from morning to evening. I was afraid of going outside in the dark, so I often held in my urine and wet the bed at night. In Hiroshima, we still had electric lights and running water, so the blackout conditions were tough to bear. Every Saturday, I would take a train home to Nakajima Honmachi, then return to Hatsukaichi on Sunday. I once told my parents, “I don’t care if I die in an air raid; I want to stay at home,” which caused them a lot of worry.

During the war, the government strictly controlled electricity, and slogans like “Luxury is the enemy” led to power consumption limits. Towns stayed dark at night due to blackouts designed to avoid becoming bombing targets. Some light bulbs were painted so they would only illuminate the space directly beneath them.

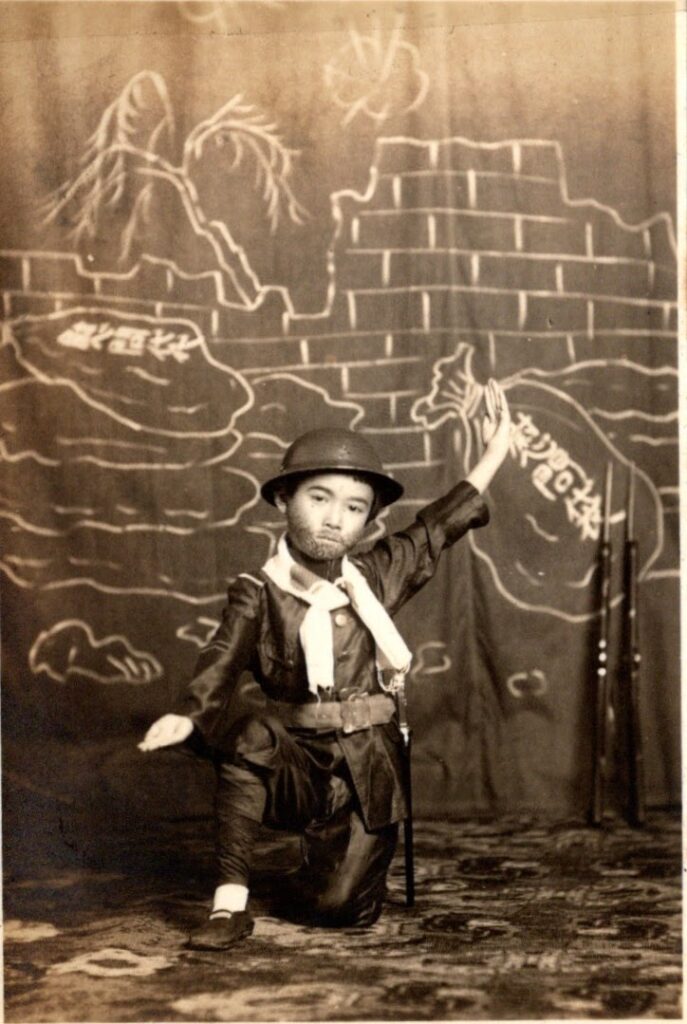

Brother and Sister

In 1939, a Nakajima dance troupe visited the Hiroshima Army Hospital.

I am third from the right in the front row, and next to me is my sister Hiroko.

You can also see my father Jiro in the back row on the left side.

My sister and brother studied hard. One day, I found out my father was going to tear down a wall on the second floor to create a study room for them. I asked him, “What about my room?” He said, “You don’t study, so you don’t need one.” Much later, a friend of my sister’s from Yasuda Kōtō Jogakkō (today’s Yasuda Girls’ Junior High School) told me my sister Hiroko was an excellent student with beautiful handwriting.

During the war, various “consolation troupes” were formed to raise soldiers’ spirits. One famous example was the “Warawashi-tai,” created at the request of Asahi Shimbun to Yoshimoto Kogyo, which performed comedy routines at the front. Local women’s associations often prepared care packages with daily necessities and sent letters of support to the troops.

“Dance performance by the Edo-kko Troupe at the Army and Navy Hospital,”

featuring nine-year-old Hamai Hiroko, taken in 1939.

wall clock

Inside Hamai Barbershop. A round wall clock can be seen in the upper right of the photo.

We had a German-made wall clock hanging on the wall. Each morning, I wound its spring, which turned counterclockwise. My father would say, “Just like your head,” meaning I was a bit contrary. Because of the 12-hour time difference with the United States, people said we had to fight “24 hours a day.” So Hiroshima City Hall gave us a sheet of paper printed with the numbers 13 through 24, telling us to stick it over the clock’s original 1 to 12. I crushed rice grains to make paste and covered the numbers one by one.

Article 73 of the “Military Internal Regulations” (Gun-tai Naimurei), enacted on August 11, 1943, states that the 24-hour system shall be used for indicating time. In the U.S. today, 24-hour notation is still referred to as “military time.”

Clock pointing to 8:15.

On August 6, I was play-fighting with toy swords at school when a sudden flash lit up the sky, the ground shook, and a mushroom-like cloud appeared. Two days later, I was told, “Stay home from school and go check on your house in Nakajima Honmachi,” so I went with my uncle. In the burnt remains, we found only a charred barber’s chair. My uncle discovered a plate clock that had been stored in the closet.

The Nakajima District, including Nakajima Honmachi, was almost completely destroyed. According to volume two of the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb War Damage Report, “It can be said that nearly everyone in the district who was present at the time was killed.” In 1956, a statue of Kannon for Peace (Heiwa no Kannon-zō) was erected in Peace Memorial Park as a memorial for neighborhood residents. In 1998, I donated the clock we found to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

The “Heiwa no Kannon-zō” (Kannon of Peace) monument built by the Nakajima Honmachi neighborhood association. A plaque listing victims’ names was also installed.

Memories of Nakajima Honmachi

Taken in 1955 on the remains of the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall.

Hamai Tokuzo is standing on the right.

Every year on August 6, we hold a memorial service on the site where Nakajima Honmachi once stood. But whenever I visit Peace Memorial Park, it makes my chest tighten. I was against preserving the Atomic Bomb Dome. That’s because, to me, the Industrial Promotion Hall was full of childhood memories—I wanted it to live on only in my mind, where it was a place of happy times.

Although the Atomic Bomb Dome was designated a World Heritage Site in 1996, there were once calls to demolish it. In the 15th year after the bombing, a high school student who was a survivor left behind a diary expressing a wish to preserve the Dome. After that diary came to light, a preservation movement began. The structure is now regularly reinforced to maintain its condition.

A recent view of the Atomic Bomb Dome from where Nakajima Honmachi once stood.

Message

I’m grateful that people from around the world come to Peace Memorial Park, but at the same time it feels as if they are treading on my parents’ and siblings’ remains. This was once a place where many people lived their everyday lives, and in a single moment, that life was taken away. If you visit Peace Memorial Park, please imagine the families and the vibrant streets that once existed here.

Slide Teaching Material: “Everyday Life in Hiroshima Before the Bombing—When the Atomic Bomb Dome Was Still the Industrial Promotion Hall”

Created by: Hayashida Mitsuhiro (RECNA Research Fellow) / Miyazaki Sonoko (Freelance Writer)

Photo Provided by: Hamai Tokuzo

Design: Okubo Maika

©Nagasaki University Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition (RECNA) / National Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Victims Memorial Museum

References and WEB sites

References / Web Resources

- Hiroshima City Hall (1971). Hiroshima Genbaku Sensai-shi (Hiroshima Atomic Bomb War Damage Report). Hiroshima City.

- Hiroshima Fieldwork Executive Committee (2017). Shōgen: Machi to Kurashi no Kioku – Nakajima Honmachi, Zaimoku-machi, Suishu-machi (Testimonies: Memories of the Town and Daily Life). Hiroshima Fieldwork Executive Committee.

- “Heiwa Kinen Kōen (Ground Zero) Machinami Fukugen-zu” (A Street Reconstruction Map of Peace Memorial Park) by Chugoku Shimbun,

https://www.hiroshimapeacemedia.jp/?page_id=25623 (accessed Feb. 20, 2023) - Kaigai Ijū Shiryōkan Dayori 2017 Haru (Overseas Migration Museum Newsletter, Spring 2017) by JICA Yokohama,

https://www.jica.go.jp/jomm/outline/ku57pq00000lx6dz-att/dayori45.pdf (accessed Feb. 20, 2023) - “Genbaku Dōmu ni Tsuite (About the Atomic Bomb Dome)” by Hiroshima City,

https://www.city.hiroshima.lg.jp/site/atomicbomb-peace/163434.html (accessed Feb. 20, 2023) - “Senchū no Seikatsu-tō wo Shiru tame no Yōgoshu (Vocabulary for Learning about Life During Wartime)” by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications,

https://www.soumu.go.jp/main_sosiki/daijinkanbou/sensai/word/index.html (accessed Feb. 20, 2023) - Iwase Harumi (2012). “‘Warau koto wa ikiru koto’—Yoshimoto Portrays Comedians at the Front,” Asahi Shimbun Digital,

https://www.asahi.com/showbiz/stage/spotlight/OSK201208150070.html (accessed Feb. 20, 2023) - “NHK Archives: Nihon News Dai 23-gō,” NHK,

https://www2.nhk.or.jp/archives/movies/?id=D0001300408_00000 (accessed Feb. 20, 2023) (accessed Feb. 20, 2023) - “Ushinatta inochi wa nidoto kaeranais (Hamai Tokuzo),” Hiroshima Speaks Out,

https://h-s-o.jp/hamai/ (accessed Feb. 20, 2023)

Learning Material

The slides can be viewed and used as teaching materials in educational settings. Download the PDF data from the bottom of the page. (Please observe the precautions noted on the slides before use.)