Everyday Life in Hiroshima Before the Bombing Hiroshima Used to Be a “Military City”

目次

- Abstract

- Chizuko Kiriake

- the poster child of war

- the Hiroshima Rikugun Hifuku Shisho.

- Mother

- Kindergarten and Nursery School

- Rabbits and Clothing

- Founder’s Day Costume Procession

- costume parade

- Work Trip to Miyajima

- A teacher of memories

- Commemorative photo at the shrine

- career woman

- atomic bombing

- Message

- References / Websites

Abstract

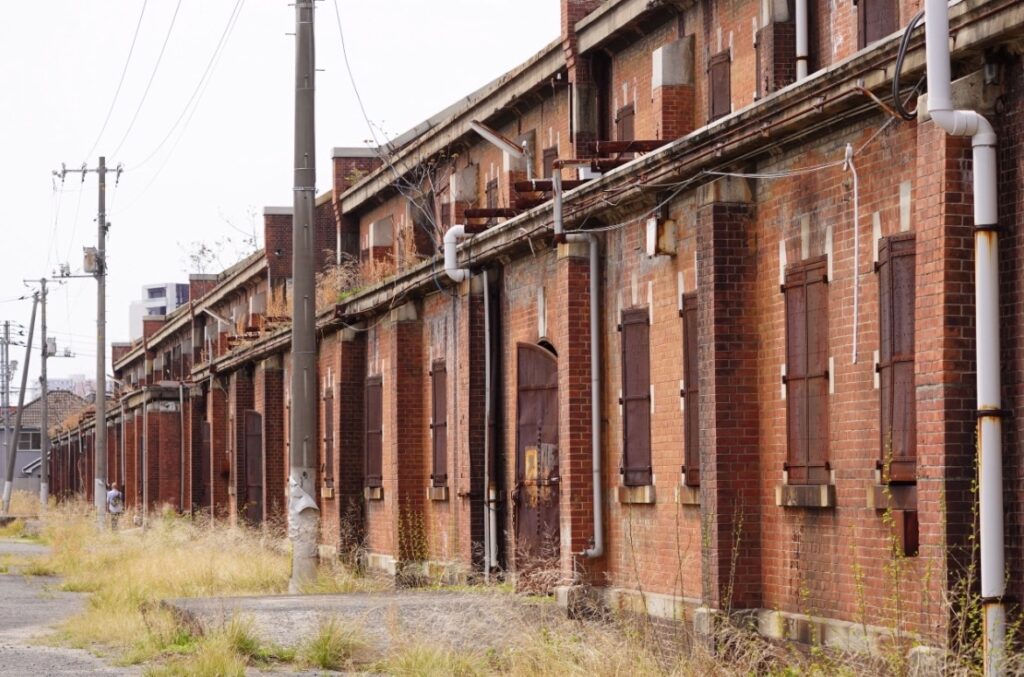

About 2.7 kilometers southeast of Hiroshima’s ground zero stands a row of four large red-brick buildings. These structures are the former Hiroshima Rikugun Hifuku Shisho—a wartime military supply factory for the Imperial Japanese Army, producing uniforms, shoes, and other necessities. They are widely known as hibaku (bombed) buildings that still bear the scars of the atomic bombing, but they also serve as war-related ruins that reveal Hiroshima’s past as a major military city.

In this slide material, we hear from Ms. Kiriake Chiezuko, who attended a kindergarten on the Hifuku Shisho premises in her childhood and later worked there under student mobilization. She talks about what school life was like during wartime, her experience in the student mobilization program, and how people lived in “Gun-to Hiroshima” (the military city).

Chizuko Kiriake

Born in 1929 under the family name Tabai. At age 15, when she was in her fourth year of kōtō jogakkō (equivalent to today’s first year of high school), she experienced the atomic bombing on a street 1.9 km from ground zero. After graduating from Hiroshima Women’s College (now Prefectural University of Hiroshima), she joined the Hiroshima Prefectural Government in 1949. At 85, she began sharing her A-bomb experience. She now speaks about her experiences at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and to student groups on school trips, working as a “hibaku taiken shōgen-sha” (atomic bomb testimony speaker).

the poster child of war

A young Kiriake Chiezuko (left)

I was born in November 1929, around the time the Great Depression began. The Second Sino-Japanese War broke out when I was in the second grade of elementary school—on Tanabata (July 7)—and the war ended when I was 15. Looking back, I lived through the war period almost entirely; you might say I was a ‘child of war.

From the Liutiaohu (Mukden) Incident in September 1931, in which the Imperial Japanese Kantō Army blew up the South Manchuria Railway tracks near Fengtian, until the defeat in 1945, Japan was continuously at war. This 15-year period is collectively known as the “Jūgonen Sensō” (Fifteen-Year War), spanning the Manchurian Incident, the Second Sino-Japanese War, and the Pacific War.

the Hiroshima Rikugun Hifuku Shisho.

One of the Hiroshima Rikugun Hifuku Shisho buildings can be seen in the background.

This commemorative photo was taken in 1935 during a costume parade on the facility’s foundation day.

I grew up in Minami-machi, Hiroshima City, where my family home still stands today. Near our house was the Hiroshima Rikugun Hifuku Shisho. The street in front of our home was called ‘Hifukushō-dōri,’ and every morning you could hear the zakku-zakku sound of people heading to work.

When the First Sino-Japanese War began in 1894, the Imperial General Headquarters was established in Hiroshima to direct the war effort. The Imperial Diet was also temporarily moved to Hiroshima, giving the city a status nearly equal to the capital. Ujina Port was expanded for sending troops to the continent, and three army supply facilities were established: the Hifuku Shisho for uniforms, the Heiki Hokyūshō for weapons, and the Ryōmatsu Shisho for food, collectively referred to as the “Rikugun Sanshō” (three army depots).

Mother

On the grounds of the Hiroshima Rikugun Hifuku Shisho. The woman on the far left is Ms. Kiriake’s mother, Tabai Mitsuko.

When I was still little, my mother started working in the Hifuku Shisho’s supply department as an accountant. She had attended Yamanaka Kōtō Jogakkō and worked at a post office, so the wife of the shōchō (head of the depot) personally invited her. Since we were living with my grandmother (my father’s mother) at the time, my mother would say, ‘Having two homemakers in one house just causes friction!

As a “branch” facility, the Hifuku Shisho was located in Hiroshima and Osaka, while the main Hifuku “honshō” was in Tokyo. According to Kigyōchi toshite no Hiroshima and Hiroshima Shōkō Yōran, compiled by the Hiroshima Chamber of Commerce, in 1924 there were 262 male and 390 female factory workers, and in 1929 there were 228 male and 277 female workers—a higher proportion of women than men.

Kindergarten and Nursery School

A group photo taken near graduation time. In the back row, sixth from the left, is Kiriake Chiezuko (marked with a pencil circle on her outfit).

I attended the daycare and kindergarten inside the Hifuku Shisho. My younger sister, who is eight years below me, was also placed there. In a later group photo, you can see many more kids, which shows that as the work got busier, more women were employed, and more children needed daycare. Young men were being sent off to war, so women filled the workforce, often doing heavy labor. That was the reality back then.

The daycare and kindergarten on the Hifuku Shisho grounds had playground equipment such as jungle gyms, slides, and swings—facilities that were quite advanced compared to typical kindergartens of the era. There was also a large public bath, medical clinic, cafeteria, employee dormitories, and even a barbershop on site, offering robust welfare benefits for workers.

Rabbits and Clothing

A memorial service for Ms. Kiriake’s maternal grandfather, held at Tokuōji Temple in Teramachi (now Hiroshima’s Naka Ward). Ms. Kiriake is in the front row, center. (Date unknown)

I’m wearing an overcoat with rabbit fur around the collar. I used to think they sheared the rabbits like sheep, but later I found out they killed them and stripped the skins to make fur collars for military coats. Realizing my coat came from a rabbit that was killed made me feel sorry for it. The uncle and aunt in this photo both died in the atomic bombing.

Many rabbits were raised on the Hifuku Shisho grounds. Children in the daycare and kindergarten enjoyed feeding them with daikon or carrot leaves. Several different breeds were kept to compare which fur provided the best insulation for the inside of military coats.

Founder’s Day Costume Procession

Commemorative photo on the founding anniversary of the Hifuku Shisho (1935).

These photos were taken before the Second Sino-Japanese War began. On the facility’s anniversary, the workers and staff would dress in costumes or form bands that went bang-bang-crash. Those three people in helmets in the middle row look like the ‘Bakudan San-yūshi’ or ‘Nikudan San-yūshi’—the original ‘tokkōtai’ (special attack units). One of them was apparently my mother.

During the January 1932 Shanghai Incident, three Japanese privates died carrying explosives to blow up barbed-wire defenses. The army praised them as “military gods” for their supposed self-sacrifice, and the press widely promoted the story as a heroic military tale (reference: Heibonsha’s Sekai Daihakken Jiten, 2nd ed.).

costume parade

A commemorative photo from another year’s costume parade. Tracks from a light railway (trolley) are visible.

You can see the ‘Nikudan San-yūshi’ in this photo, too. People here loved costume parades and held them often. We also had sports days and film screenings, setting up a screen in front of the warehouse. This building was still a warehouse, but it’s gone now. The only ones that remain are the four red-brick buildings numbered 10 through 13.

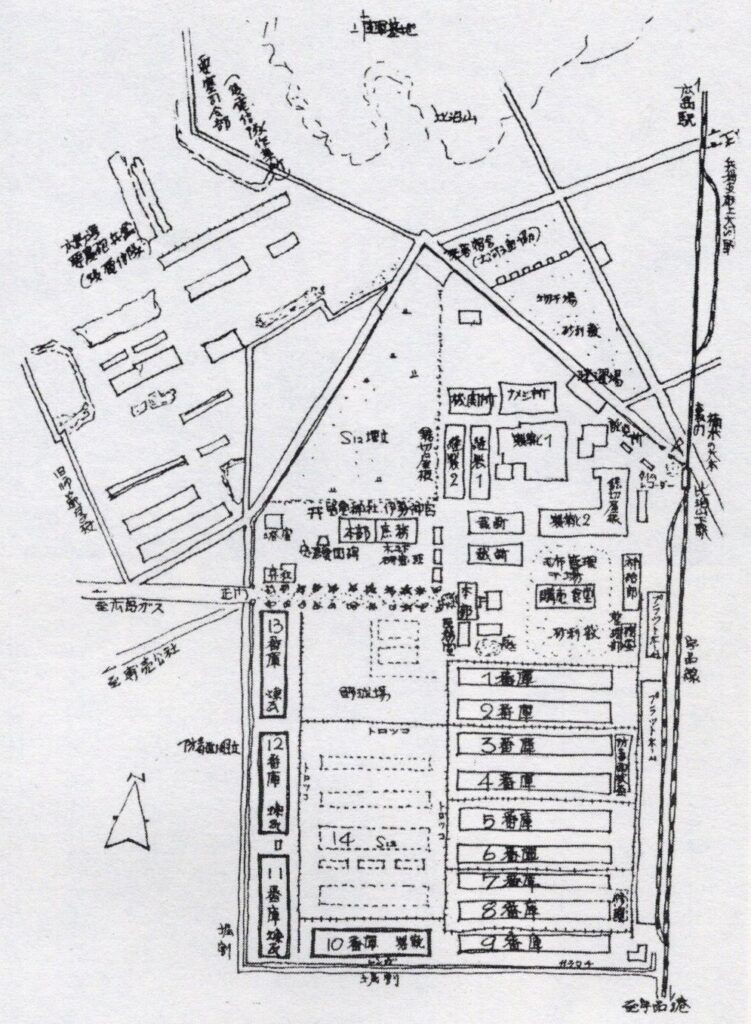

The Hiroshima Rikugun Hifuku Shisho once had nine more warehouses, plus headquarters, cutting, sewing, and other buildings for various tasks. A narrow-gauge railway (trolley) ran through the compound, and on its eastern edge was a platform connected to the north-south Ujina Line.

“Hiroshima Rikugun Hifuku Shisho Layout”

Drawn by Hashimoto Hideo

Work Trip to Miyajima

Autumn 1937: Ms. Kiriake’s mother Mitsuko (second from the left) on a workplace trip from the Hifuku Shisho to Miyajima, holding Ms. Kiriake’s little sister who was eight years younger. The Great Torii (O-torii) is visible behind them.

Here’s a photo from when my mother, who was in charge of payroll, went on a trip to Miyajima with her supervisors. The Second Sino-Japanese War started on Tanabata Day that same year. Ujina Port, which sent out military ships to the Chinese mainland, was close by, so we often went to wave Hinomaru flags and shout ‘Banzai!’ as soldiers departed. Whenever news came of another victory, there would be a lantern parade. It was a booming time back then.

Hiroshima Port (also called Ujina Port) developed from around 800 years ago as a gathering place for tribute rice shipments near the Ota River mouth. In 1894, it was expanded for military use during the First Sino-Japanese War and the Russo-Japanese War, becoming a key launching point for sending soldiers and supplies to the Korean Peninsula and China.

A teacher of memories

Minami Elementary School, third grade, 1938. Ms. Kiriake is at the far left of the third row from the front.

The woman teacher in the center was scary, but the man next to her was a ‘kyōsei no sensei,’ a trainee from a teachers’ college. He was very kind, and everyone loved him. We all clung to him during recess. Later, at a class reunion, we heard rumors he had died on the Chinese front.

Although this was a public elementary school, only girls are shown in the photo because in those days, classes were divided by gender starting in the third grade. This custom traces back to an old Chinese teaching, “Danjo shichisai ni shite seki wo onaji uzusezu,” meaning boys and girls over age seven should not sit together, reflecting the prevailing view that boys and girls should be separated.

Commemorative photo at the shrine

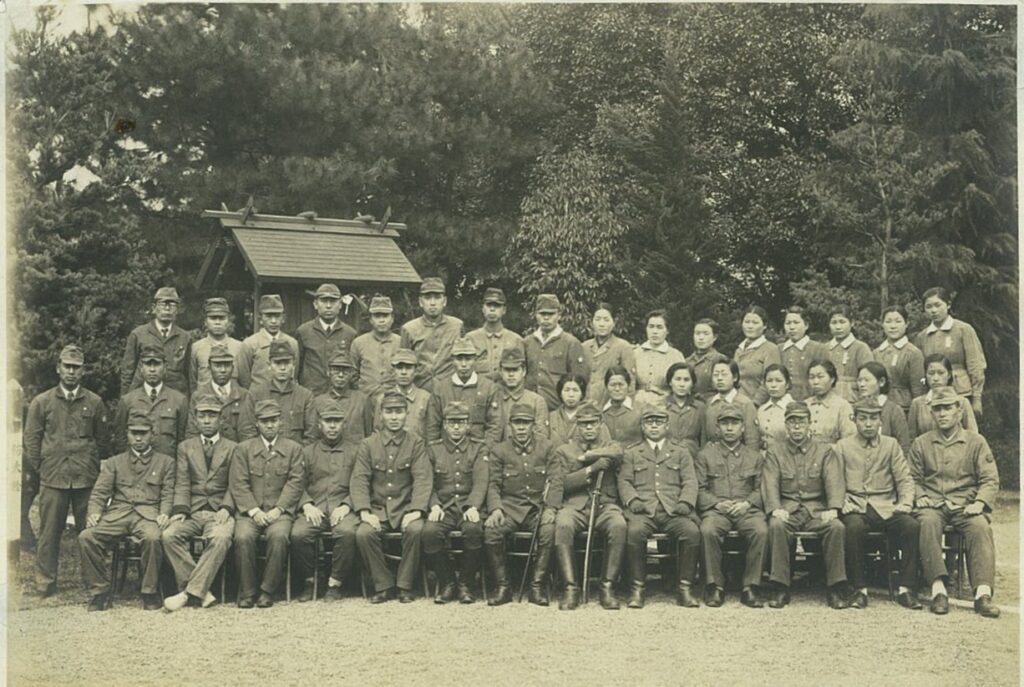

Employees of the Hifuku Shisho Supply Department Headquarters (August 1944). In the middle row,

fifth from the right, is Ms. Kiriake’s mother.

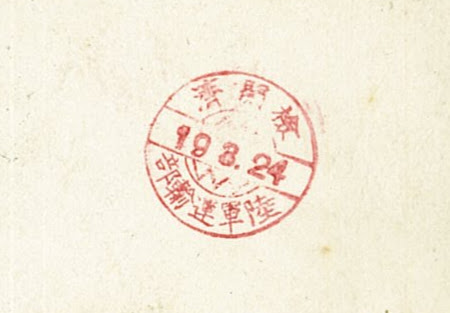

Inside the Hifuku Shisho gates, there was a small shrine called Minami Jinja, enshrining the spirit of Ise’s Kōtaijingū. There was a big field around it. I’m not sure why this particular commemorative photo was taken, but there is a censor’s stamp on the back.

Under the 1941 “Rinjishobun Chōsa Tori-shimari Hō” (Temporary Controls on Speech, Publications, Meetings, and Organizations), freedom in these areas was heavily restricted. Even photographs were subject to censorship, and any gatherings or associations required permission. This censorship ended after the war, but was followed by new restrictions under the Allied Occupation.

career woman

December 1, 1943: A commemorative photo when Ms. Kiriake’s mother Mitsuko (35 at the time) transferred from the payroll section to the cashier section, seated front row center.

At a time when most women wore monpe pants, my mother and her colleagues always wore skirts. Now I realize they were early ‘career women.’ She had many subordinates. After the war, she helped returning evacuees. She used to say, ‘They called me a traitor for only bearing daughters who wouldn’t go to war, but thank goodness I had girls because they never had to fight.’

After World War II, the Ministry of Health and Welfare (later the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare) established local Repatriation Relief Bureaus on November 24, 1945, in 11 locations, including Ujina, Sasebo, and Hakata, to assist Japanese returning from China, the former Soviet Union, and elsewhere. By the end of 1946, more than five million people had returned to Japan, and large-scale group repatriations continued until 1958.

atomic bombing

U.S. Army photo / from the U.S. National Archives / courtesy of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

Post-bombing view of central Hiroshima.

At the far right, a white patch circled in the photo indicates the Hiroshima Rikugun Hifuku Shisho.

As a student mobilized to the Hifuku Shisho, I washed military uniforms with holes or bloodstains on them, wondering how we could possibly win the war this way. I wasn’t there when the atomic bomb fell, but my mother carried my injured grandmother from our home to one of the Shisho warehouses.

Most buildings within 2 km of the bomb’s hypocenter were destroyed, but the Hifuku Shisho, 2.7 km away, narrowly remained standing. Many injured people took refuge there. A horrifying account of the warehouse interior can be found in Tōge Sankichi’s “Sōko no Kiroku” (Record of the Warehouse).

(April 2, 2023) The remaining four red-brick warehouses of the former Hiroshima Rikugun Hifuku Shisho.

Message

We must never again let young people who bear the future die in war. We need everyone to think about what we can do to prevent this, work together, and protect peace. Peace will not simply come to us while we sit by in silence. We have to pull it in, seize it, and guard it with all our strength—otherwise, it will vanish like foam on water.

Created by: Hayashida Mitsuhiro (RECNA Research Fellow) / Miyazaki Sonoko (Freelance Writer)

Photos Provided by: Kiriake Chizuko Design: Okubo Maika

© Nagasaki University Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition (RECNA) / National Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Victims Memorial Museum

References / Websites

- Yasui Sankichi (2016). “‘Jūgonen Sensō’ to ‘Ajia Taiheiyō Sensō’ no koshō to sono tenkai ni tsuite” [On the Terminology and Evolution of the “Fifteen-Year War” and “Asia-Pacific War”], Gendai Chūgoku Kenkyū, vol. 37, pp.81–99.

- Kyū Hifuku Shisho no Hozen wo Negau Kondankai, ed. (2020). “Kyū Hifuku Shisho no Hozen wo Negau Kondankai,” Aka Renga Sōko wa Kataritsugu — Kyū Hiroshima Rikugun Hifuku Shisho Hibaku Shōgen-shū [The Red-Brick Warehouses Bear Witness: A Collection of A-Bomb Testimonies from the Former Hiroshima Rikugun Hifuku Shisho].

- Abe Yasunari, Katō Kiyofumi (2004-5). “‘Hikiage’ to iu Rekishi no Toikata (Jō)” [Approaches to the History of “Repatriation” (Part 1)], Hikone Ronso, no. 348, pp.129–154.

- Tōge Sankichi (2016). Genbaku Shishū [Poems of the Atomic Bomb]. Iwanami Shoten.

- Kiriake Chiezuko (2019). Hiroshima wo Ikinuite [Living Through Hiroshima]. No More Hibakusha Kenshō Center Hiroshima.

- Kiriake Chiezuko (2021). Hiroshima wo Ikinuite Part 2. No More Hibakusha Kenshō Center Hiroshima.

- Hiroshima City Hall, ed. (1971). Hiroshima Genbaku Sensai-shi [Hiroshima Atomic Bomb War Damage Report]. Hiroshima City.

Websites

- “Tatemono no Higai (Building Damage)” by Hiroshima City,

https://www.city.hiroshima.lg.jp/soshiki/48/9401.html (Accessed March 20, 2023) - “History of Hiroshima Port” by Hiroshima Prefecture,

https://www.pref.hiroshima.lg.jp/soshiki/221/portofhiroshimahistory.html (Accessed March 20, 2023) - “Kyū Hiroshima Rikugun Hifuku Shisho” by Hiroshima Prefecture,

https://www.pref.hiroshima.lg.jp/site/hihukushisyo/ (Accessed March 20, 2023) - “Kyū Hiroshima Rikugun Hifuku Shisho Sōko Tokusetsu Saito” by ArchiWalk Hiroshima,

https://www.oa-hiroshima.org/hifuku/hifuku.html (Accessed March 20, 2023) - “Nisshin Sensō to Hiroshima” by Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum,

https://hpmmuseum.jp/modules/exhibition/index.php?action=DocumentView&document_id=84&lang=jpn (Accessed March 20, 2023) - Kigyōchi Toshite no Hiroshima (Taishō 15 edition) by Hiroshima Chamber of Commerce, 1926. National Diet Library Digital Collection,

https://dl.ndl.go.jp/pid/963933 (Accessed March 20, 2023) - Hiroshima Shōkō Yōran (Shōwa 4 edition) by Hiroshima Chamber of Commerce, 1929. National Diet Library Digital Collection,

https://dl.ndl.go.jp/pid/1100668 (Accessed March 20, 2023)